How To Find All URLs on a Domain

Whether you're running an SEO audit, planning a site migration, or hunting down broken links, there's one task you'll inevitably face – finding every URL on a website. It sounds simple, but it isn't. Search engines don't index everything, sitemaps are often outdated, and dynamic pages hide behind JavaScript. This guide walks you through every major discovery method, from quick Google search operators and no-code scrapers to custom Python scripts.

Justinas Tamasevicius

Last updated: Feb 09, 2026

16 min read

Method 1: The technical basics (sitemaps & robots.txt)

Before reaching for enterprise crawling tools, start with what websites give you directly: their robots.txt file and XML sitemaps. These are the fastest ways to get a baseline list of a website's pages. They're specifically designed to declare a site's structure to search engines and crawlers.

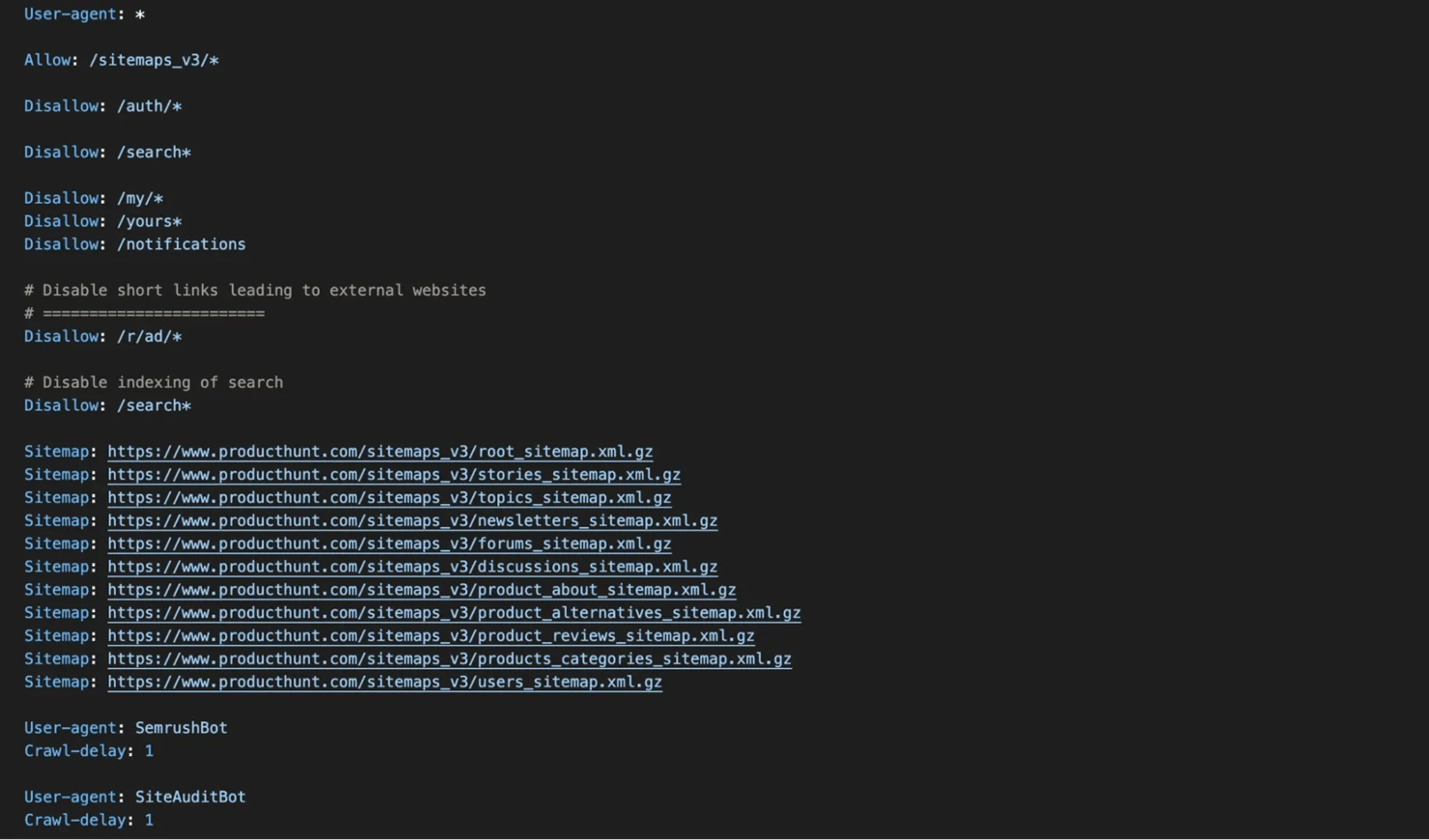

Checking robots.txt

The robots.txt file lives at the root of every domain. To find it, simply append /robots.txt to any URL:

Open this URL in your browser, and you'll see a plain text file with directives that tell crawlers which pages they're allowed (or not allowed) to access. Here's what a typical robots.txt looks like:

What to look for:

Directive

What it tells you

User-agent:

Different rules for different crawlers (Googlebot, Bingbot, etc.)

Allow:

Exceptions to disallow rules.

Disallow:

Paths the site doesn't want crawled, which often reveal hidden sections like /auth/, /admin/, or /internal/.

Sitemap:

Direct links to the site's XML sitemaps, your primary source for URL discovery.

Locating and parsing XML sitemaps

If robots.txt doesn't list a sitemap (many sites forget to include it), try these common locations:

- /sitemap.xml

- /sitemap_index.xml

- /sitemap.xml.gz (compressed version)

- /sitemaps/sitemap.xml

- /wp-sitemap.xml (WordPress sites)

- /sitemap.txt (plain text list of URLs, common on Shopify)

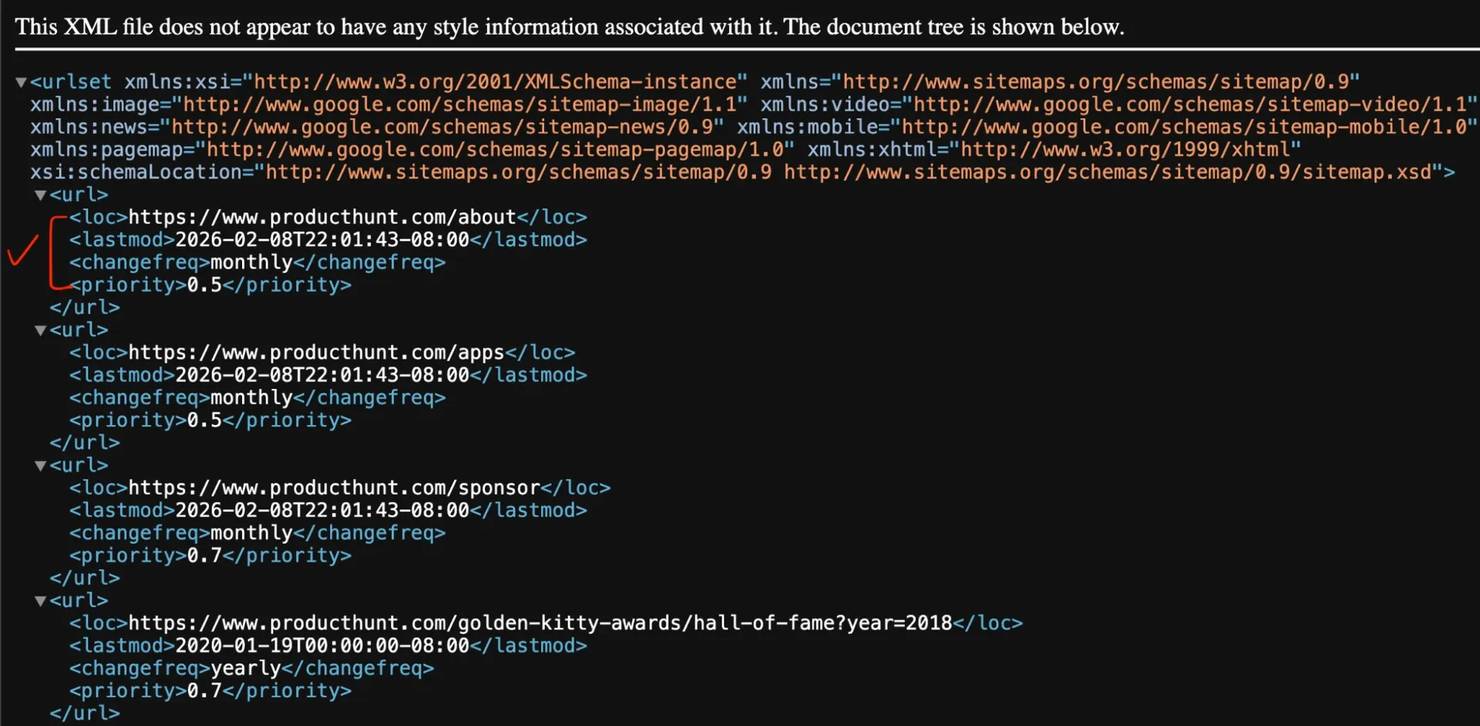

Open the sitemap URL in your browser. You'll see XML that looks like this:

Key elements:

- <loc> – the actual URL (this is what you're after)

- <lastmod> – when the page was last modified

- <changefreq> and <priority> – suggest how often a page changes and its relative importance, but Google officially ignores both tags. Don't rely on them for SEO decisions.

Handling sitemap index files

Because the standard protocol limits a single sitemap to 50,000 URLs (or 50MB), large websites use a sitemap index that points to multiple sub-sitemaps:

You'll need to fetch each sub-sitemap and extract the URLs from each one. (See Method 4 for a Python script that handles this automatically.)

Quick sitemap parsing (no code required)

If you just need to grab URLs from a sitemap without writing code, several free tools can help:

- Screaming Frog has a dedicated sitemap mode (covered in Method 2).

Google Sheets – use IMPORTXML() function:

Note: this formula times out on large sitemaps (2,000+ URLs) and fails on sites with anti-bot protection like Cloudflare.

The limitation of sitemaps: they only contain what the site owner has chosen to include. Sitemaps are often outdated, incomplete, or missing pages that exist but were never added. That's why you'll often need to combine sitemap parsing with actual crawling.

Method 2: SEO crawling tools (no coding required)

If you want to find all pages on a website without writing a single line of code, dedicated crawling tools are your best bet. They systematically follow every link on a site and build a URL inventory.

However, crawlers can't find "orphan pages", pages with no internal links pointing to them. To discover orphan pages, cross-reference with Google Search Console, Analytics data, or parse your server access logs for Googlebot activity.

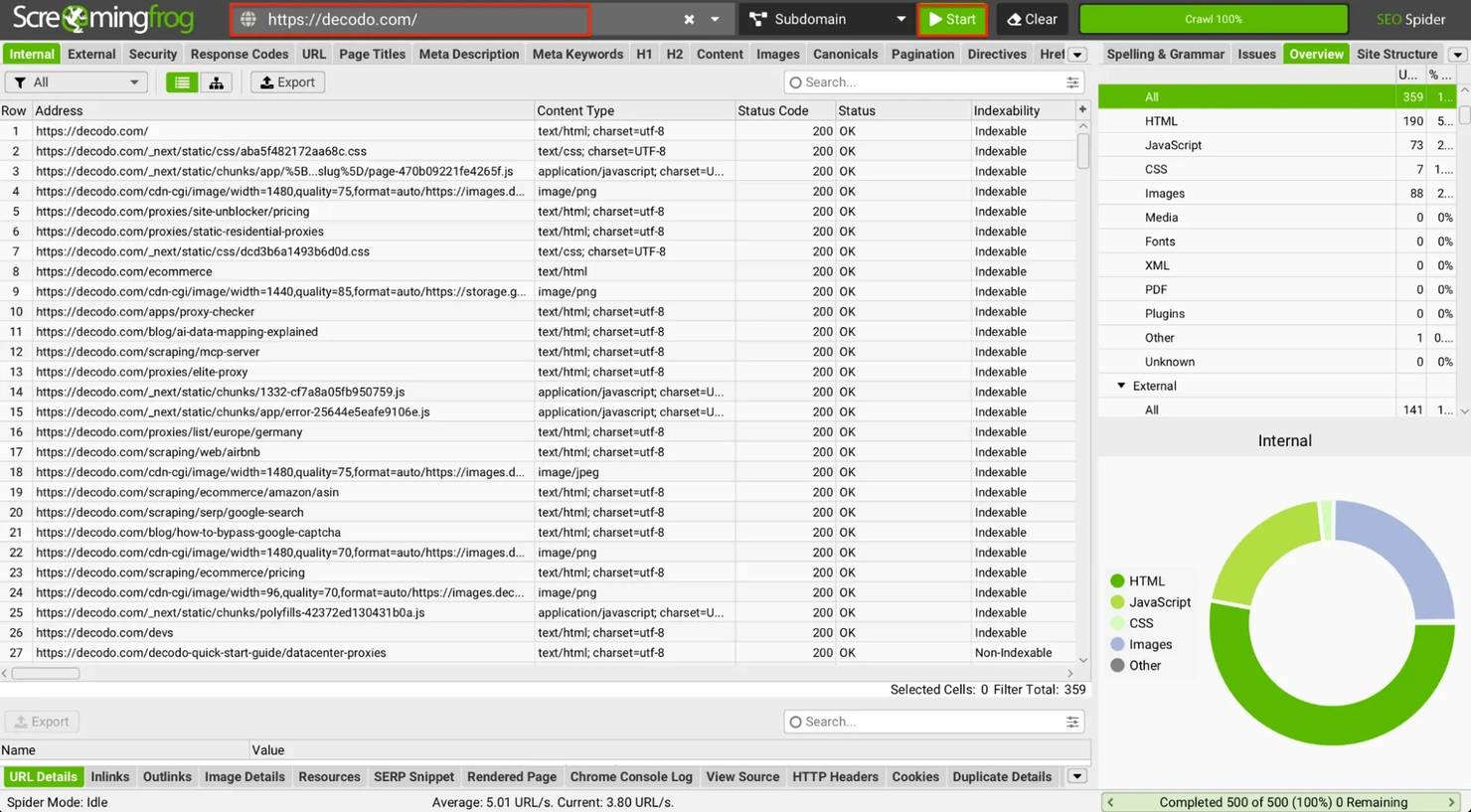

Screaming Frog SEO Spider

Screaming Frog is one of the most widely adopted industry standards for website crawling. It's a desktop application that works on Windows, Mac, and Linux.

How to use it:

- Download and install from the official website.

- Enter the target URL in the search bar at the top.

- Click Start.

- The crawler will instantly begin following every internal link, cataloging every reachable URL (pages, resources, documents), and presenting them in a structured table.

Exporting your URLs:

Once the crawl completes, click the Export button on the Internal tab to download a CSV containing every discovered URL.

Limitations:

- The free version caps crawling at 500 URLs.

- For larger sites, you'll need a paid license (currently ~$279/year).

- No built-in proxy rotation: because it runs on your desktop, it uses your local IP address. If you try to crawl a site with advanced anti-bot protection (like Cloudflare or Datadome), your IP will get blocked instantly.

- Heavy on local RAM: JavaScript-rendered crawling requires launching headless Chrome instances on your machine, which can take more computer resources on large sites.

Method 3: Google search operators & no-code automation

Sometimes you don't need every URL, just a quick way to see every page on a website that Google knows about, or a specific subset of pages. Google search operators give you that instantly.

Google search operators (the quickest method)

Open Google Search and type:

This returns every page Google has indexed for that domain. The number shown under the search bar gives you an approximate count of indexed URLs.

Advanced operators to narrow your search:

Operator

What it does

Example

site:

Shows all indexed pages from a domain

site:example.com

site: inurl:

Finds pages with specific URL patterns

site:example.com inurl:blog

site: intitle:

Finds pages with specific words in the title

site:example.com intitle:pricing

site: filetype:

Finds specific file types

site:example.com filetype:pdf

site: -inurl:

Excludes pages with certain URL patterns

site:example.com -inurl:login

Useful combinations:

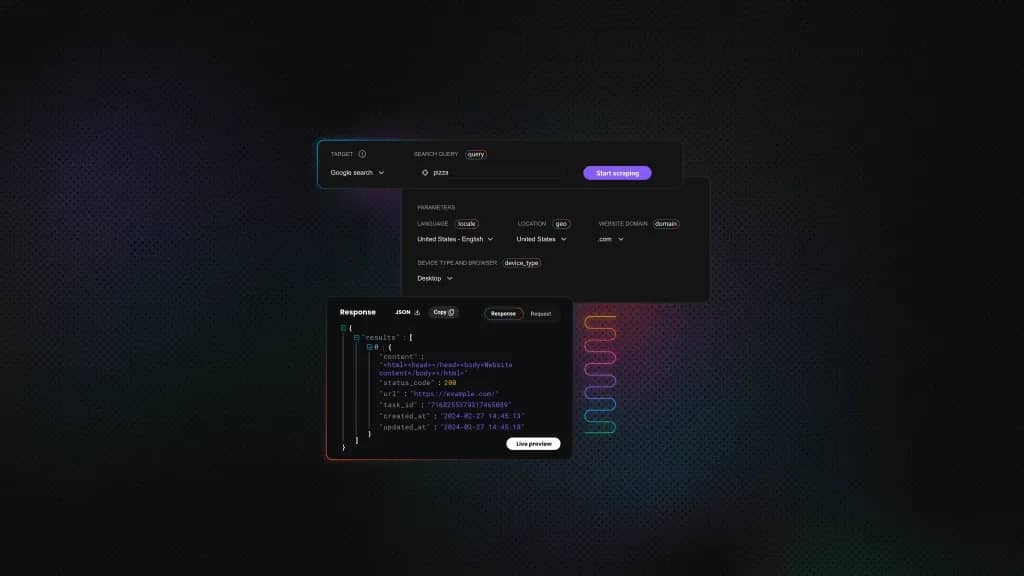

The limitation: Google only shows what it's indexed. Pages blocked by robots.txt, marked as noindex, or simply not yet discovered won't appear. This method also caps display results at around 400 URLs, so very large sites will be incomplete. To extract these URLs at scale without getting blocked by Google's CAPTCHAs, use a dedicated SERP Scraper API.

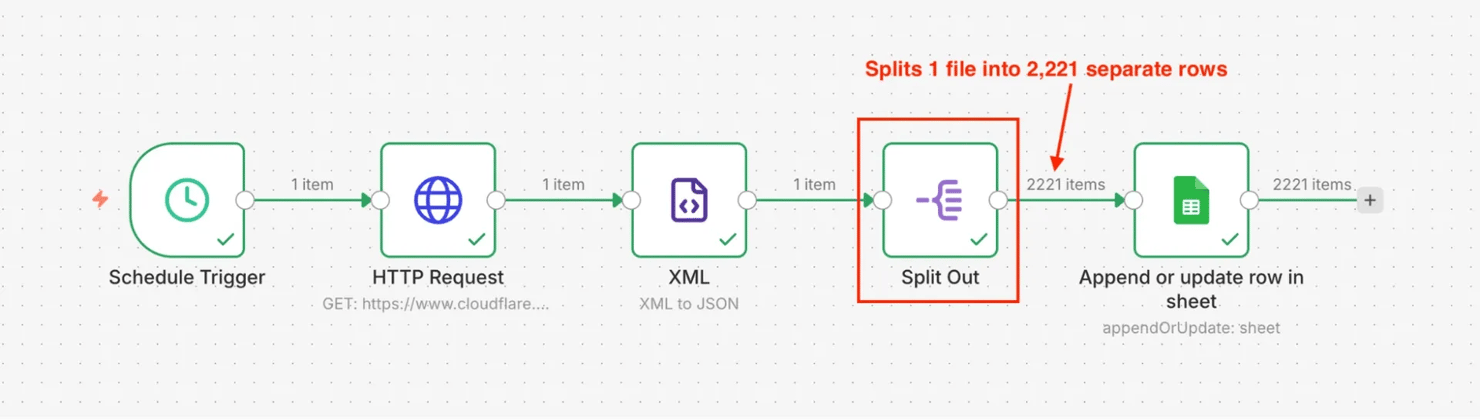

No-code automation with n8n

If you need to regularly monitor URLs or automate the collection process without coding, workflow automation tools like n8n can help.

Example workflow for sitemap monitoring:

- Schedule Trigger – runs the workflow daily or weekly

- HTTP Request node – fetches the sitemap XML

- XML node – parses XML to JSON and extracts all <loc> elements

- Item Lists node (Split Out) – splits the array into individual items (critical: without this, you get 1 row with all URLs)

- Google Sheets node – saves each URL as a separate row

If you don't want to build this from scratch, download the pre-built n8n JSON template and import it directly into your n8n workspace.

This approach lets you track URL changes over time, new pages added, and old pages removed, without manual intervention.

What n8n can do:

- Fetch and parse sitemaps on a schedule

- Send alerts when new pages are added or when pages disappear

- Export data to Google Sheets, Airtable, or databases

Note: n8n's XML-to-JSON node loads the entire sitemap into memory. For large sitemaps (50,000+ URLs), this can crash or timeout the workflow execution. Split oversized sitemaps into batches or use a dedicated script (see Method 4).

Limitations of native n8n HTTP requests:

- Struggle with JavaScript-heavy sites (SPAs built with React, Vue, or Angular)

- Can be blocked by anti-bot protections

- Limited control compared to custom scripts

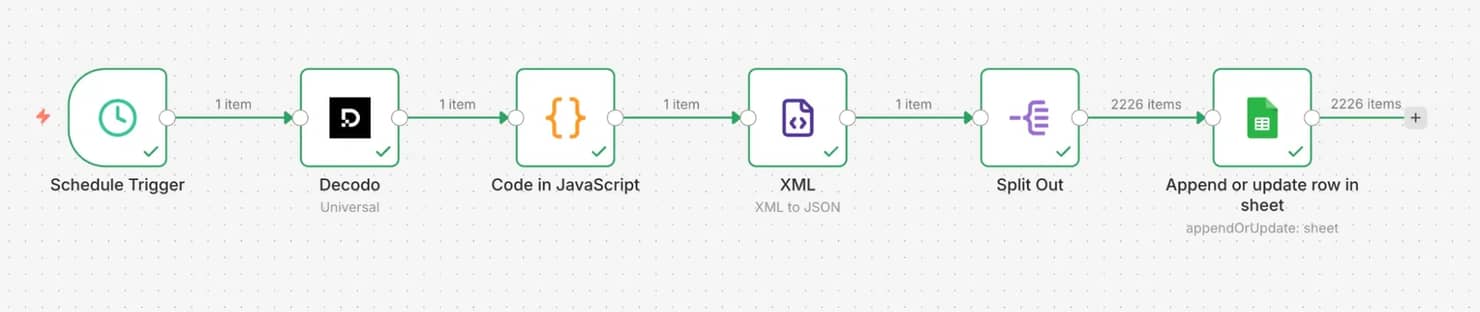

The solution: if you hit these walls, pair n8n with a scraping API that handles JS rendering and anti-bot bypasses. Decodo offers a native n8n integration for this.

You can import this workflow directly into your n8n workspace.

Use no-code when you need ongoing monitoring rather than a one-time crawl. Native n8n HTTP requests work well for sites with reliable sitemaps or simple HTML. For JS-heavy or protected sites, pair n8n with a scraping API that handles rendering and anti-bot protection.

Method 4: Building custom scripts (Python & Node.js)

When off-the-shelf tools hit their limits, the site is too large, too complex, or requires specific logic, it's time to build your own crawler. Building your own crawler also means you're responsible for managing server infrastructure, rotating proxies, and constantly updating selectors when target sites change their structure.

Solution A: Sitemap extraction script

This script fetches a sitemap and extracts all URLs, handling regular sitemaps, sitemap index files, and gzip-compressed sitemaps .xml.gz.

Required libraries:

Here’s the code:

What this script does:

- Fetches the sitemap XML with proper headers.

- Automatically decompresses gzip-compressed sitemaps .xml.gz.

- Tracks visited sitemaps to prevent infinite loops from circular references.

- Detects sitemap index files and recursively processes sub-sitemaps.

- Saves everything to a CSV file.

Usage:

Alternative parsing libraries:

- xmltodict – converts XML to Python dictionaries, which some developers find easier to work with than Beautiful Soup for pure XML parsing.

- ultimate-sitemap-parser – a specialized library that handles edge cases like compressed sitemaps, malformed XML, and automatic sitemap discovery from robots.txt.

If you prefer JavaScript for sitemap parsing, here's a modern script using ESM imports and native fetch (Node.js 22+).

Required packages:

Here’s the code:

Usage:

Examples:

Note: for massive sitemaps (100k+ URLs), this in-memory approach may exceed Node's default heap limits. For enterprise production, refactor this to use Node.js Stream's response.body.getReader() to process chunks dynamically.

Solution B: Full site crawler with Scrapy

When a site doesn't have a sitemap, or the sitemap is incomplete, you need to crawl the site by following links. Scrapy is a powerful, production-ready framework that handles concurrency, rate limiting, and link extraction efficiently.

Required libraries:

Here’s the code:

Key features of this Scrapy crawler:

- High concurrency – handles 16 simultaneous requests by default.

- Built-in rate limiting – configurable download delay between requests.

- Configurable robots.txt handling – set to False in this example for maximum discovery coverage.

- Automatic link extraction – uses CSS selectors for fast parsing.

- Domain filtering – only follows links within the same domain.

- Smart filtering – skips images, CSS, JavaScript, and admin paths.

Usage:

Examples:

Why Scrapy over Requests? Scrapy is purpose-built for web crawling. It handles connection pooling, automatic retries, redirect following, and concurrent requests out of the box. For serious crawling projects, Scrapy is significantly faster and more robust than standard synchronous implementations using requests.

Note: Run this as a standalone script (e.g., python site_crawler.py), not as an imported module inside another Python file. Scrapy's internal event loop shuts down permanently after a crawl finishes, so calling crawl_site() a second time in the same process will throw an error.

Solution C: Fast JavaScript crawling with Crawlee

The Scrapy crawler above works great for traditional websites, but it can't see content rendered by JavaScript. For Single Page Applications (SPAs), you need a headless browser.

Crawlee is a modern crawling library that wraps Playwright with auto-scaling parallel execution. It's 5x to 10x faster than basic Playwright because it runs multiple browser pages simultaneously.

Required libraries:

Here's the code:

Usage:

Examples:

While Scrapy uses lightweight HTTP requests, Crawlee spins up entire Chrome browsers in the background.

Key differences between Scrapy and Crawlee:

Scrapy

Crawlee

Speed

Fast (100s of pages/min)

Medium (10 to 50 pages/min)

JavaScript

Can't execute

Full JS support

Concurrency

Request-level

Browser page-level (auto-scaling)

Memory

Low (~50MB)

Medium (~100MB per parallel page)

Use case

Static HTML sites

SPAs, React, Vue, Angular

Use Crawlee only when you've confirmed that Scrapy returns empty or incomplete pages. For less intensive tasks, go with Scrapy as it's a much faster solution. Switch to Crawlee only for JavaScript-rendered content.

Tip: Running headless browsers locally is RAM-intensive and easily fingerprinted by anti-bot systems. If you'd rather skip infrastructure management, managed scraping APIs (like Decodo) can return fully rendered HTML via a single API call.

When to use custom scripts:

- The site has no sitemap or an incomplete one

- You need to crawl more than 500 pages (Screaming Frog's free limit)

- You need custom logic (specific URL patterns, authentication, etc.)

- You want to integrate URL discovery into a larger pipeline

- You're building a recurring monitoring system

Addressing common challenges & advanced scalability

Real-world URL discovery rarely goes smoothly. As you scale from crawling small sites to enterprise-level projects, you'll encounter predictable obstacles. Here's how to overcome each one.

Challenge 1: Missing sitemaps

Problem: many websites don't have a sitemap at all, or their sitemap is severely outdated and missing hundreds of pages.

Solution: implement a web crawling script that starts at the homepage and discovers links dynamically. Rather than relying on what the site owner has declared, you follow every internal link to build a complete picture.

This is exactly what the Python crawler in Method 4 does. It:

- Starts at a seed URL (usually the homepage).

- Parses all <a> tags to find internal links.

- Adds new links to a queue.

- Repeats until all discoverable pages are visited.

Scaling tip: for large sites, use the concurrent crawling approach with ThreadPoolExecutor (Python) or Promise.all (Node.js) to crawl multiple pages simultaneously while respecting rate limits.

Challenge 2: JavaScript-heavy websites (SPAs)

Problem: standard libraries like requests (Python) or axios (Node.js) only fetch raw HTML. They can't execute JavaScript. This means Single Page Applications built with React, Vue, or Angular appear nearly empty.

When you fetch a typical React app with standard requests, you get this blank shell:

The navigation, product listings, blog posts, everything, is generated by JavaScript that standard scrapers never execute.

Solution 1: Crawlee with Playwright. As detailed in Method 4 (Solution C), you can use a headless browser framework like Crawlee to actually render the JavaScript before extracting the links. Trade-off: this requires managing heavy server infrastructure and high RAM usage.

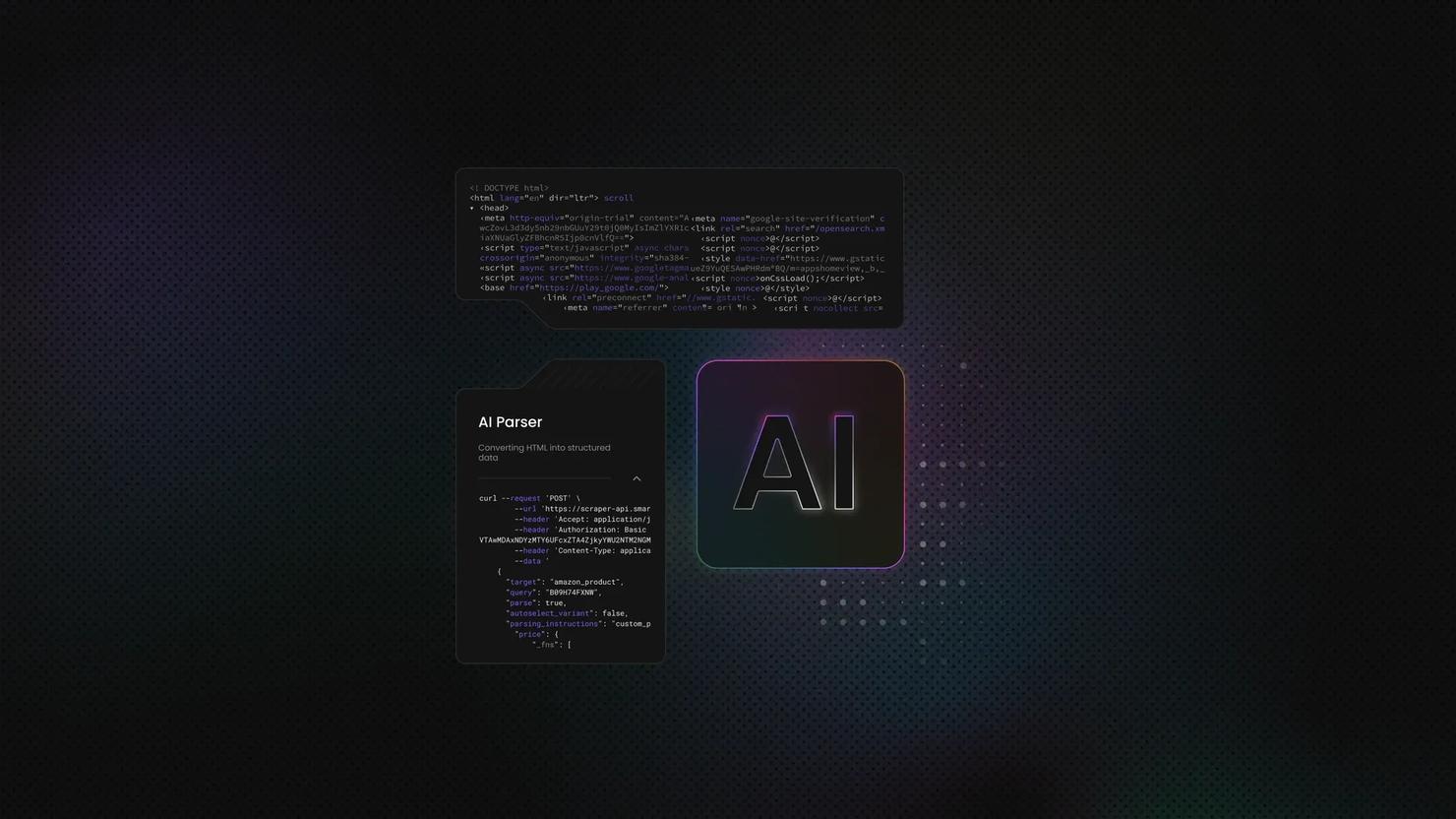

Solution 2: Scraping APIs with JavaScript rendering (recommended). For large-scale crawling without managing infrastructure, scraping APIs offer a simpler approach. Instead of managing browser instances yourself, you make a single API call with a JS rendering parameter:

This approach eliminates browser management entirely – the API renders JavaScript server-side and returns the final HTML to your script.

Challenge 3: Anti-bot blocking & rate limits

Problem: websites protect themselves from aggressive crawling. Making too many requests too quickly triggers anti-bot systems, resulting in:

- 403 Forbidden – you've been identified as a bot (Cloudflare, Akamai, DataDome)

- 429 Too Many Requests – you've exceeded the rate limit

- CAPTCHA challenges – the site wants to verify you're human

- IP bans – your IP address is blocked entirely

Solution 1: Basic countermeasures (browser fingerprinting)

Start by mimicking real user traffic. Anti-bot systems immediately flag requests missing standard browser headers:

Solution 2: Managed proxy & scraping services

Headers only get you so far. For serious crawling projects, you need IP rotation to prevent bans. Managed services like Decodo handle proxy rotation, automatic retries, and CAPTCHA bypassing so you don't have to build that infrastructure yourself.

Scaling considerations

As your crawling needs grow, consider these architectural patterns:

Scale

Approach

Recommended stack

1,000 to 10,000 pages

Concurrent crawling

Python asyncio or Node.js Promise.all

10,000 to 100,000 pages

Distributed queue

Celery, Redis queue, multiple workers

100,000+ pages

Managed infrastructure

Decodo Web Scraping API, serverless functions

Key scaling principles:

- Control request concurrency – hitting a server with 500 requests per second is the fastest way to get your IP banned. Implement limits to crawl politely without triggering DDoS protection.

- Implement exponential backoff – when you hit a 429 error, wait progressively longer before retrying (e.g., 2s, 4s, 8s).

- Cache aggressively – store HTML responses locally in Redis or S3 so you don't re-crawl identical pages unnecessarily.

- Monitor error rates – track success rates by domain. If your 403s spike, your current proxy pool has been burned and needs rotation.

What to do after collecting URLs

Now that you have a comprehensive map of your target website, the raw URL data is your baseline. Here's how enterprise teams operationalize this data:

1. Large-scale SEO audits

Feed your URL list into an auditing pipeline to check status codes (404s, 301 redirects) and extract metadata at scale. Finding orphaned pages or missing canonical tags is impossible without a complete URL baseline.

2. LLM & AI training data

Raw URLs are the starting point for building proprietary datasets. Feed your URL list into a headless scraper to extract the raw text and HTML, which is then used for AI and LLM training and custom knowledge bases.

3. Competitor content gap analysis

By mapping a competitor's entire URL structure, you can reverse-engineer their content strategy. Categorize their URLs by subfolder (e.g., /blog/, /features/, /integrations/) to discover which content pillars they're investing in heavily, and where your own site is lacking.

4. Flawless site migrations

When redesigning an enterprise website, a single missed redirect can destroy years of SEO value. Your scraped URL list acts as the master checklist to ensure every old page is successfully mapped to its new destination.

Final thoughts

Finding every URL on a website doesn't have to be a manual nightmare. Whether you are using a simple Google search operator or building a massive Scrapy pipeline, the key is matching the right method to the scale of your project.

If you're scaling beyond what scripts and free tools can handle, Decodo's Web Scraping API can take the infrastructure burden off your plate. Try it free and see how it fits your workflow.

Scale your URL discovery

Handle JavaScript sites and anti-bot blocks automatically.

About the author

Justinas Tamasevicius

Head of Engineering

Justinas Tamaševičius is Head of Engineering with over two decades of expertize in software development. What started as a self-taught passion during his school years has evolved into a distinguished career spanning backend engineering, system architecture, and infrastructure development.

Connect with Justinas via LinkedIn.

All information on Decodo Blog is provided on an as is basis and for informational purposes only. We make no representation and disclaim all liability with respect to your use of any information contained on Decodo Blog or any third-party websites that may belinked therein.